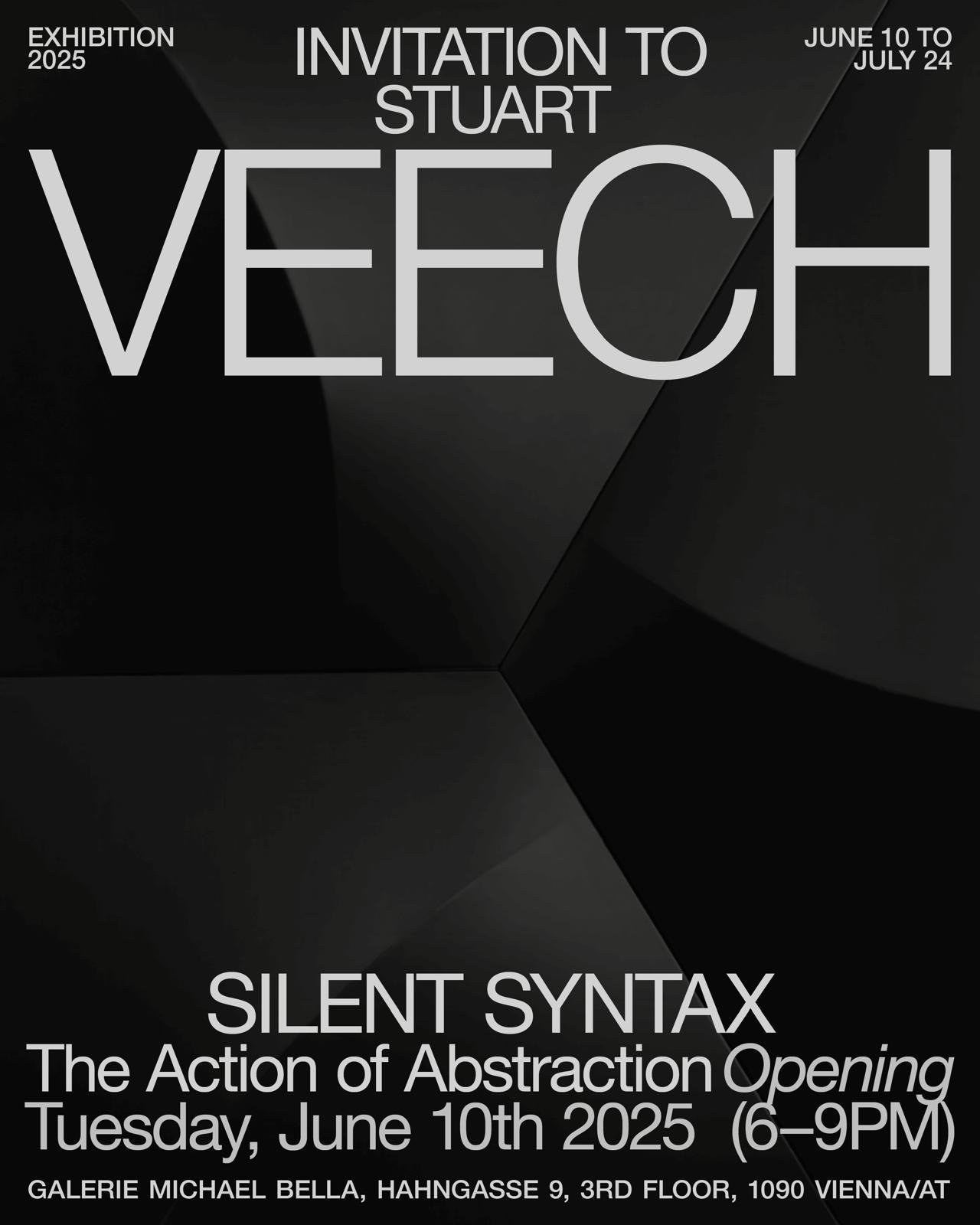

Silent Syntax – The Action of Abstraction

Stuart Veech

June 10 - July 24 2025

The exhibition Silent Syntax marks the culmination of the curatorial cycle Beyond Existence by carrying the series’ conceptual trajectory to its most radical condensation: a passage from the manifest structures of political, linguistic, and spiritual existence to the silent architectures that precede them. If the earlier exhibitions mapped tensions between subjectivity and the external world, language and power, and myth and transformation, Silent Syntax retracts from these thematic surfaces into the conditions of form themselves, toward the unspoken structures that make experience possible. In this final articulation, abstraction is offered as an operative mode of human action, a way of structuring the world prior to meaning.

This movement reflects a deeper philosophical necessity. Traditionally, abstraction has been tethered to the contemplative, immaterial sphere, as if its distance from figuration marked a withdrawal from the world. But in Silent Syntax, abstraction is refigured as the condition of world formation itself. What was once cast in opposition to action, a mode of distillation, idealization, or philosophical retreat, is reclaimed as an architectural principle: as structuring of cognition.

This reframing calls into question the old division between vita activa and vita contemplativa. While Hannah Arendt famously places thought outside the realm of action (silent, internal, withdrawn (Arendt 1958, 11–12)), Veech’s work forces a reconsideration. His modular reliefs, rotational systems, and spatial articulations do not speak; they structure. These don’t fabricate objects in the traditional sense; they configure the perceptual and cognitive fields through which objecthood itself becomes intelligible. Thought here is not excluded from action; it becomes action.

The stakes of this operation become clearer when considered through Peter Sloterdijk’s theory of spherology, which posits space as an existential structure: the condition for any form of subjectivity, intimacy, or world-relation (Sloterdijk 1998, 28–31). Veech’s works enact such spaces: they construct relational micro-spheres in which perception, orientation, and material interaction co-produce appearance. These are dynamic enclosures, open to movement and restructured by presence.

Henri Lefebvre’s theorization of space as socially and mentally produced (La production de l’espace, 1974) lends additional weight. For Lefebvre, space is never a passive background to action; it is already action, produced by rhythms, relations, and forces (Lefebvre 1991, 26–29). The same is true in Veech’s reliefs, which materialize space through subtle dislocations and modular tensions. The viewer does not stand apart from these works: they inhabit their instability, participating in the event of space as such.

Gilbert Simondon’s philosophy of individuation provides another critical axis. For Simondon, the individual is not a completed form;it’s a metastable system of tensions: a field in which form, matter, and information co-constitute one another through processes of becoming (Simondon 1964, 23–30). Veech’s works are precisely such fields: they present structured potentials. Each encounter, each shift in light or bodily position, activates a new phase of individuation, and stability is continuously deferred.

The choice to frame the exhibition through the term “syntax” rather than “form” or “structure” is not incidental. Syntax implies a rule-based generation of relations that precedes meaning, a pre-semantic organization of elements that makes meaning possible without signifying. In linguistic terms, syntax governs the possible without determining the actual. In Veech’s works, syntax governs the modular, rotational, and spatial possibilities without collapsing them into fixed statements. Each relief, each spatial configuration, proposes a field of potentiality, rather than a completed form. The viewer looking at these works doesn’t decode a meaning as much as inhabitand negotiate a structure.

Jean-François Lyotard’s reflections on the “inhuman,” the operations of systems that precede, exceed, or suspend human expressibility, offer a final lens through which to understand the stakes of Veech’s abstraction. In The Inhuman: Reflections on Time (1988), Lyotard suggests that the inhuman is not only technological alienation but also the silent operations of structures that underlie human cognition and temporality (Lyotard 1991, 1–7). Veech’s syntax operates at precisely this level: silently structuring perceptual and cognitive space without announcing itself discursively. His use of abstraction is not simply “minimal” or “geometric”; it is an exposure of the silent infrastructures that sustain sense itself.

Silent Syntax folds the Beyond Existence cycle back onto itself, exposing the conditions of appearance, relation, and existence that had been at stake all along. In Veech’s silent architectures, abstraction reclaims its place within the sphere of action as the operative structuring of the world’s very possibility.

-

Stuart Veech’s practice compels a revision of what we consider action to be. His work insists that abstraction, often assumed to be theoretical, disembodied, or even escapist, must be understood as a form of action. In The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt draws a sharp line between thinking and acting. She places thought within the vita contemplativa, outside the sphere of human affairs, which she reserves for labor, work, and action, each grounded in visibility, productivity, or natality (Arendt 1958, 11–12). But this separation depends on a conception of action that begins with language, with the deed, and with the intersubjective scene. What Veech’s practice shows is that action can take place at a prior, structuring level in the field of sense.

The viewer’s encounter with Veech’s modular and spatial works is not an act of interpretation but of negotiation: spatial, cognitive, and embodied. The work exposes a syntax to be inhabited, and abstraction here is a proximity with the generative infrastructure of experience. This is why the works never stabilize: they shift under the movement of light, the movement of the body, and the spatial logic of their rotation. Stability and meaning are here suspended, and what remains is structure in the active, verb-like sense of structuring.

The movement of structuring, as an active unfolding rather than a fixed condition, draws attention to the lines along which this process proceeds. The internal organization of Veech’s modular and spatial constructions is not only an arrangement of static forms but an orchestration of relational vectors: each module, each plane, each intersection inscribed along a trajectory of lines that enact. Timothy Ingold’s reflections on the ontology of the line offer a critical interlocutor here, expanding the concept of line from a graphic or geometric element into a generative principle through which worlds are made, unmade, and remade. In Lines: A Brief History, Ingold proposes that the line is a movement, a trace of passage, an articulation of becoming; to live, he writes, “is to be immersed in a world of lines” (Ingold 2007, 1). Veech’s structures, in this sense, emerge from the weaving, intersecting, and overlapping of lines whose trajectories shape both material articulation and spatial negotiation. The modularity at stake here is relational, not additive: each module is a node along a structural line that connects, deflects, bifurcates, and extends.

Ingold distinguishes between the line that is drawn and the line that is walked, between the inscription and the path, and between the trace and the thread (Ingold 2007, 41). Veech’s lines oscillate across these registers, structuring the experience of space as an unfolding movement. The viewer’s engagement with these works is a continuous repositioning along the vectors the lines articulate: lines that cut across material planes, lines that generate perceptual thresholds, and lines that organize relational fields. In The Life of Lines, Ingold extends this reflection, describing the meshwork as an entanglement of lines “in which any point is a knot in a bundle of lines” (Ingold 2015, 3). Veech’s silent syntax operates as such a meshwork: each structural element is a knot in a bundle of trajectories whose crossings and tensions organize the architectural, material, and perceptual field.

The linear structures embedded in Veech’s modular syntax operate: they enact the silent architecture through which space is structured, relation is activated, and perception is modulated. Ingold’s understanding of line as generative, as relational, as ontological trajectory foregrounds the extent to which Veech’s practice is grounded in structuring: a continuous, silent unfolding of relations traced along the movement of lines.

Henri Lefebvre’s theory of space as socially and mentally produced helps to clarify this. As he writes in La production de l’espace, space is not an empty container into which bodies and meanings are placed; space is a product of practices, relations, and cognitive formations (Lefebvre 1991, 26–29). In this sense, Veech’s structures generate space. The viewer’s perceptual, bodily, and orientational engagement is co-constitutive of it, and space is enacted as an ongoing event: a shifting field of tensions and calibrations without finality.

Gilbert Simondon’s philosophy of individuation furthers this shift. For Simondon, the individual is a metastable field: a system in dynamic tension, in which form, matter, and energy co-constitute one another (Simondon 1964, 23–30). This logic of becoming (of constant, differential modulation) is the logic Veech’s works inhabit. Each new orientation, each encounter with light or body or proximity, produces a new phase of individuation and structures of potential undergoing continuous activation.

Sloterdijk’s spherological model, previously introduced, reappears here to be reactivated. If human life is always embedded in spheres, relational spaces that sustain subjectivity, then Veech’s works function as spherological modules: enclosures that operate by interaction. These are matrices that structure. The viewer enters a dynamic topology of reflective surfaces, modular interlockings, and cognitive provocations, spatiality becoming something that moves through you.

What these works enact is a reflexive structuring of experience. Dieter Henrich, in his analysis of reflexive self-consciousness, argues that thought does not simply appear, that it must constitute itself through a recursive operation, one that is structural and not discursive (Henrich 1982, 4–8). Veech’s works externalize this recursion: they are thinking, spatialized, and suspended in material configuration. The viewer does not “reflect” on the work; they are drawn into the work’s own process of reflexive articulation.

This silent operation, neither expressive nor communicative, touches what Jean-François Lyotard terms the inhuman: the structuring operations that make human cognition possible but do not belong to it as content (Lyotard 1991, 1–8). The inhuman is not a negation of the human but its condition: the impersonal field that precedes narrative precedes subjectivity. Veech’s abstraction inhabits this threshold without narration or resolve, making the non-verbal infrastructure of appearing visible.

In this way, abstraction reclaims its rightful place within the field of action. Silent Syntax names this possibility: that thought, far from being excluded from the world of action, might be its very ground.

-

The abstraction realized in Silent Syntax does not announce itself through semantic references or symbolic signs; it operates at a more fundamental level: through the structural articulation of form, space, and movement prior to any assignment of meaning. Stuart Veech’s practice constitutes a syntax without language: a relational grammar in which modularity, rotation, surface dynamics, and light interact to structure perception itself (Bois and Krauss 1997, 13).

The formal and optical proximity between Stuart Veech’s modular reliefs and the shaped surfaces of Agostino Bonalumi presents an immediate but ultimately misleading point of comparison. Bonalumi, working from the late 1950s onward, developed a practice of “extroflexion”: the deformation of the monochromatic canvas by pushing and shaping it from behind, generating volumetric protrusions that break the continuity of the pictorial plane (Corà 2013, 17–19). These interventions produce ambiguous spatialities: the viewer’s eye oscillates between the visual smoothness of the surface and the sculptural presence of its distortions, between painting and relief, image and object (Pola 2015, 45–47). Light becomes an operative agent, sliding across the monochrome expanses, intensifying or diminishing the perception of depth depending on angle and movement (Vettese 2002, 66–68). Bonalumi’s work thus stages a phenomenological encounter, one in which the viewer’s perception is drawn into a play of surface tensions without abandoning the formal coherence of the painting as a unified object.

Yet despite these apparent affinities, Veech’s modular constructions operate on an entirely different register. Where Bonalumi’s extroflexions retain the canvas as their primary site of intervention, Veech’s works abandon the pictorial framework altogether. His modules construct spatial relations, generating dynamic fields through rotational offsets, material asymmetries, and cognitive dislocations. Bonalumi’s shaped surfaces, however spatially active, remain materially bounded, producing a stable objecthood animated by pressure points (Corà 2016, 102–104). Bonalumi’s approach remains fundamentally painterly, working with traditional materials and treating the surface as a painted, visually modulated skin. His extroflexions produce pressure points that deform the canvas locally, generating spatial tensions through sculptural protrusions. Veech, by contrast, constructs his forms with a full structure operating beneath and through the material. Veech’s architectures destabilize the very conditions of stability: modular components interact structurally, producing metastable systems in which relational drift, perceptual recalibration, and spatial negotiation become constitutive operations.

This distinction is decisive. While Bonalumi’s practice expands the painting into the third dimension, proposing a continuity between image and object, Veech’s modular syntax suspends the category of the object entirely, constructing dynamic, open-ended fields that cannot be resolved into a single visual or material unity (Pola 2015, 51–52). The light interactions diverge sharply: Bonalumi’s painted surfaces respond to illumination through chromatic modulation and shadow play, while Veech’s industrial constructions absorb, refract, and deflect light in ways that emphasize material density, opacity, and architectural presence. The viewer of Bonalumi’s work confronts a shaped, tactile entity whose formal presence is immediately graspable even as its surface shifts under changing light. The viewer of Veech’s reliefs, by contrast, is drawn into a recursive negotiation with structural instabilities that resist final resolution, demanding not contemplation but cognitive and bodily activation.

This approach necessarily invites dialogue with the historical legacy of minimalism, but it does so with significant critical divergences. While minimalist artists of the 1960s (Donald Judd, Carl Andre, and Anne Truitt) sought to eliminate illusionism and narrative, affirming the material presence of the object within real space, Veech radicalizes this inquiry by destabilizing objecthood itself (Meyer 2001, 55). His works, they generate shifting fields of relational tensions, in which form cannot be stabilized without movement, orientation, and temporal engagement (Crary 1999, 24).

Donald Judd’s notion of the “specific object” provides a crucial historical anchor. In his 1965 essay of the same name, Judd argues for a new category of artwork, neither painting nor sculpture, that occupies space directly, emphasizing factuality over illusion (Judd 2005, 181–189). Judd’s structures insist on orthogonality, modular repetition, and industrial fabrication, producing objects that remain constant despite the viewer’s movement around them. In Judd’s minimalism, materiality and spatial placement are fixed: the object declares itself fully and immediately, resistant to interpretative destabilization (Buchloh 1990, 98).

Veech’s syntax subverts this fixity from within. His modules, though seemingly stable, introduce conditions of asymmetry, rotational offset, and light-responsive surfaces that prevent the establishment of a definitive objecthood. The works resist being grasped as “specific objects” in Judd’s sense. They unfold instead as dynamic fields: metastable constructions that continually defer closure. While Judd’s boxes and progressions define space through repetition and serial structure, Veech’s modules generate space through the viewer’s negotiation of perceptual instability. Presence in Veech’s work is not given; it is constituted through movement, through the shifting negotiation between eye, body, and surface (Krauss 1979, 51).

The question of form’s autonomy and extension, central to Veech’s structural concerns, finds a historically significant precedent in Ellsworth Kelly’s shaped canvases and color fields. Yet the relation is neither direct continuation nor simple influence; it is a dialogue that must be carefully reconstructed in terms of formal mechanics rather than superficial resemblances (Bois 1996, 150–152).

Ellsworth Kelly’s early project sought to emancipate form and color from the compositional hierarchies of European modernism. His works of the late 1940s and 1950s already indicate a fundamental shift: color and shape are not subordinated to pictorial composition; they are independent, self-sufficient presences that assert themselves directly within space. In Colors for a Large Wall (1951), for instance, Kelly arranges colorsas an open field: a modular structure without hierarchical center, foreground, or background (Kelly 1993, 12–17).

This anti-compositionality is crucial. In Kelly, the boundaries of the form are determined by external limits: the edge of the canvas, the wall, and the field of vision. The work continues conceptually beyond its material support. Each form is both complete and incomplete: sufficient unto itself, yet always suggesting an extension beyond its immediate presence (Kelly 1993, 22).

Veech’s engagement with these questions is more radical. Where Kelly’s forms imply extension as a conceptual operation, a thought experiment of spatial continuation, Veech’s reliefs embody extension as a material and perceptual event. His modules, rotations, and shifting light dynamics physically enact the instability of form’s boundaries. The viewer experiences continuation beyond the object through bodily negotiation. The field is no longer a cognitive inference; it’s a spatial and temporal unfolding (Bois and Krauss 1997, 15–18).

Moreover, Kelly’s shaped canvases, despite their innovations, remain fundamentally frontal. Their autonomy operates in the plane of the wall: flatness persists as a condition of visibility. Veech’s structures, by contrast, operate volumetrically. Their relief surfaces protrude into space, demanding movement not only across a plane but around and along axes of depth. The syntax of modularity, offset, and rotation transforms the viewer’s relation to the work from contemplation to navigation (Colomina 1992, 136).

While Kelly’s shaped abstractions dismantled the compositional logic of painting, Veech extends this dismantling into the architecture of experience itself. The relation is one of structural intensification: Veech pushes the implications latent in Kelly’s work into a full spatial and cognitive activation (Bois 1996, 153).

The problem of form’s stability and its structural destabilization through internal operations finds a second critical historical locus in Frank Stella’s early shaped canvases, particularly those of the Protractor Series (1967–1971). Stella’s practice, while often grouped within minimalism, opens another line of inquiry that is crucial for understanding Veech’s syntax: the tension between structural rigor and optical dynamism (Friedman 1986, 78).

In the Protractor Series, Stella abandons the rectangular support of traditional painting in favor of canvases shaped according to internal compositional logics. Circles, interlaced arcs, and angular fields are deployed to generate an environment of optical rhythms. Crucially, the shape of the canvas is no longer support; it’s produced by the internal movement of forms themselves (Stella 1970, 32–35). The boundary is a consequence of the painting’s internal syntax.

This internal production of boundary destabilizes the viewer’s perceptual anchoring. The regularity of Stella’s geometric systems, the repetition of arcs and stripes, is continually disrupted by the asymmetries of scale, curvature, and spatial tension inherent in the shaped canvas. The eye is set into motion across surfaces that both affirm and undermine the expectation of uniformity (Stella 1986, 114).

Veech’s engagement with these structural mechanisms is profound but decisively transformed. Where Stella’s shaped canvases induce optical movement within a fundamentally planar and frontal structure, Veech extends this destabilization into the spatial and bodily dimension. His reliefs are volumetric constructs that demand physical negotiation. Rotation, modular offset, and surface tactility introduce actual spatial shifts rather than optical illusions (Bois and Krauss 1997, 19).

Where Stella’s works assert the autonomy of surface through color and pattern, Veech’s reliefs dismantle surface as a stable category altogether. The interplay of material modulation and light, especially the black surfaces that fluctuate between matte absorption and reflective activation, produces a spatial indeterminacy that cannot be resolved at a single point of view.

Veech introduces a dimension of rotational dynamism that Stella’s works only prefigure. While the Protractor Series suggests circular movement through optical means, Veech realizes it structurally: modules and forms rotate, shift, and reposition themselves relative to gravitational and spatial axes. Rotation in Veech’s practice is not a metaphor; it is a physical operation that alters the cognitive geometry of the work at every moment (Foster 1996, 39).

Stella’s shaped canvases opened the pictorial surface to internal logic and optical movement, while Veech radicalized this opening, dissolving the surface into spatial dynamics, replacing optical rhythms with structural and cognitive displacements. His works are architectures of movement and thought (Meyer 2001, 57).

The destabilization of form through subtle asymmetries and incomplete structures finds another crucial historical articulation in the work of Robert Mangold. Mangold’s practice, particularly from the mid-1960s onward, challenges the assumption that minimalist geometry must be synonymous with closure, regularity, or systematic completeness. Instead, Mangold’s works stage a tension between formal precision and deliberate fragmentation — a tension that profoundly resonates with Stuart Veech’s concerns (Mangold 2000, 41).

Mangold’s shaped canvases, such as Ellipse (1973) or Attic Series (1990), reject the pure regularity of the square or rectangle in favor of forms that are visibly constructed yet inherently imperfect. He employs simple geometries (circles, ellipses, rectangles) , but disrupts their internal coherence: lines do not complete their arcs, symmetry is suggested but withheld, and divisions are introduced at irregular intervals (Mangold 2000, 7–12). These structural interruptions are the work’s operative logic, and form exists here in a state of potentiality.

In Mangold, the viewer encounters a kind of formal hesitation: shapes assert themselves, but their authority is undermined from within. Geometry becomes contingent: a fragile, human construction rather than a Platonic ideal. The experience of Mangold’s works involves navigating this tension between expectation and interruption, order and incompleteness (Bois 1996, 149).

Veech builds upon this principle but radicalizes its implications for spatial experience. While Mangold’s asymmetries operate within a fundamentally planar and frontal logic (the painting as surface confronting the viewer) Veech’s structures project this destabilization into three-dimensional and temporal space. The viewer’s movement reveals shifting asymmetries that cannot be resolved from a single perspective. Each change in position, each inflection of light, rearticulates the relational field (Colomina 1992, 138).

Where Mangold’s asymmetries are inscribed graphically through the drawn line against the surface, Veech’s asymmetries are embedded materially and structurally; they are the operations of the support itself, the rotations of mass and surface in physical space. As such, instability is materially realized (Meyer 2001, 60).

This shift from graphic to structural asymmetry is decisive. In Mangold, the viewer remains in front of the work, engaging its internal tensions through visual attention. In Veech, the viewer becomes implicated within the field of asymmetry itself, moving through relational instabilities that are both spatial and cognitive. There is no external position from which to stabilize the work’s form; the work remains in continuous negotiation with the subject’s perception and movement (Foster 1996, 37).

Mangold introduced a productive instability into the minimalist vocabulary; Veech, on the other side, amplifies this disequilibrium into a full spatial and temporal architecture, his reliefs depicting the fragility of form and constructing it as a lived, embodied experience.

The reconfiguration of surface as an active, dynamic field — rather than a static boundary — finds a pivotal historical articulation in the work of the ZERO Group, particularly in the practices of Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, and Günther Uecker. Emerging in postwar Germany, the ZERO artists sought to revive abstraction and to redefine the material and perceptual conditions of the artwork itself. Their experiments with light, surface modulation, and optical instability opened new avenues for understanding form as an event rather than a fixed entity, a premise that profoundly undergirds Veech’s structural concerns (Glöckner 2008, 29–32).

Heinz Mack’s early reliefs and “light dynamizations” are exemplary. In works such as Dynamische Struktur (1959), Mack deploys parallel ridges and undulating surfaces to transform the material support into an active agent of light modulation. Light is no longer incidental to the work; it becomes its primary material. The surface behaves as a field of shifting reflections and shadows, contingent on the viewer’s position and the ambient illumination (Mack 2011, 18–22). Otto Piene’s “light ballet” installations and perforated surfaces similarly dissolve the static object into dynamic interplay with spatial and temporal forces.

Crucially, the ZERO artists rejected the idea of the artwork as a self-contained object. Instead, they proposed the artwork as an open system: a relational field in which materiality, light, and perception continuously co-produce meaning. This relationality was not metaphorical but physical: viewers moving through space experienced the instability of surfaces as a direct bodily phenomenon. Surface ceased to be a boundary; it became a generator of spatial events (Glöckner 2008, 91).

Stuart Veech’s practice extends and deepens these insights, but with decisive shifts. Like the ZERO artists, Veech treats surface as an active participant in the construction of perceptual space. His use of rubberized black surfaces, textured modulations, and rotating forms generates fields of light and shadow that fluctuate with the viewer’s movement. However, while ZERO’s surfaces often operated through optical flicker and rhythmic repetition, Veech’s surfaces operate through structural dynamism and material depth (Glöckner 2008, 34).

In Veech’s reliefs, light is not simply reflected or scattered across a textured plane; it is modulated through volumetric articulations. Surface and depth intertwine: convexities, concavities, and tilts introduce a spatial complexity that exceeds optical play. The viewers observe shifting patterns of light while they experience a restructuring of spatial orientation itself. Movement through the space surrounding the work produces visual changes and also shifts in cognitive anchoring—an active recalibration of perceived form (Colomina 1992, 138).

Veech’s integration of rotational movement also introduces a temporal dynamism absent in the original ZERO experiments. In Mack and Piene, the viewer’s movement and the light’s fluctuation are sufficient to activate the work; in Veech, the object participates in movement. Rotation destabilizes the geometry of form, producing shifting asymmetries and relational reconfigurations that unfold over time. The surface ceases to be merely reactive; it becomes an agent of structural transformation (Glöckner 2008, 37).

Veech inherits the ZERO Group’s commitment to surface as an active field, and he transforms this commitment into a full spatial and temporal architecture. His works stage the instability of light on surface; they construct dynamic, metastable fields where surface, depth, movement, and perception are in continuous negotiation (Glöckner 2008, 94).

Across these multiple historical dialogues — Judd’s specific objects, Kelly’s autonomous forms, Stella’s shaped canvases, Mangold’s fragile geometries, and the ZERO Group’s activated surfaces — Silent Syntax articulates a decisive transformation. Stuart Veech’s works participate in these traditions while restructuring their operative principles at a more fundamental level (Meyer 2001, 61).

The logic of modularity, once associated with repetition and serial objecthood, becomes in Veech a syntax of dynamic relation. His modules are elements in a shifting grammar of form, light, and movement. Rotation destabilizes the apparent symmetry of structures, exposing the tension of perceptual anchoring. Light transforms material presence, introducing temporal dynamics that continuously reconfigure spatial relations (Foster 1996, 41).

This operational syntax constructs metastable fields — relational architectures that demand the viewer’s movement, attention, and cognitive recalibration. Stability, if it occurs, is provisional and contingent, not structural. Perception itself becomes an act of world construction: a silent negotiation of modular tensions, rotational shifts, and surface transformations (Bois and Krauss 1997, 21).

Importantly, Veech’s works insist on the materiality of these operations: they are grounded in the specific behaviors of rubberized surfaces, modular joints, rotational mechanics, and surface tension. The syntax of Silent Syntax is silent not because it withdraws from materiality, but because it operates at the level of material-relational structures that precede linguistic articulation (Crary 1999, 28).

Silent Syntax extends, therefore, the project of abstraction beyond the historical limits of minimalism and post-minimalism. It proposes a new field of structural action: one in which form is generated, in which space is produced, andin which perception is constitutive. In this structural field, abstraction becomes an operative act : a silent syntax that structures the world without speaking it (Krauss 1979, 55).

This logic of silent structuring — of modular production, spatial destabilization, and cognitive activation — sets the stage for the next development: the intersection of architectural thought and the disruption of space.

-

While Stuart Veech’s practice draws primarily on architectural strategies of structuring space, another crucial lineage emerges through the engineered object modularity initiated by Robert Rauschenberg. Particularly in his Combines (1954–1964) and later Scenarios and Cardboards series, Rauschenberg approached objects as assemblies of differentiated, often conflicting components — engineered to coexist in unstable, relational structures.

In Rauschenberg’s Combines, the fusion of painting, sculpture, and found material does not seek to unify disparate elements into a harmonious whole. Instead, it preserves their tension: painting stretches against sculptural protrusion, two-dimensionality collides with objecthood, and surface yields to depth unpredictably (Krauss 1999, 42–48). These works introduce a logic of assemblage that is neither collage nor synthesis: the components remain heterogeneous, and their relations remain unstable.

Rauschenberg’s later constructions increasingly reflect an engineered logic: components designed to fit together structurally. Works such as Oracle (1962–65)—a monumental, sound-emitting assemblage — demonstrate a principle where mechanical, material, and perceptual systems are integrated into a working whole without collapsing their internal differences (Forge and Hopps 1991, 88–91).

This principle of “engineered modularity”—the precise construction of relational instability — provides a crucial model for understanding Veech’s modular syntax. In Silent Syntax, each module, surface articulation, and rotational mechanism is meticulously engineered to sustain a metastable field of perceptual shifts. Modules are constructed to operate relationally: to rotate, offset, and produce asymmetrical tensions without disintegration (Colomina 1992, 135).

Yet Veech’s departure from Rauschenberg is decisive. While Rauschenberg’s assemblages revel in the material heterogeneity and associative excess of found objects, Veech pursues a principle of material unity. His works are materially disciplined: the use of uniform surfaces, controlled textures, and restricted color (black rubber) ensures that relational instability arises structurally rather than associatively (Meyer 2001, 57).

Whereas Rauschenberg’s assemblages invite interpretative proliferation — the found objects resonate with cultural, social, or symbolic associations — Veech’s modules refuse such proliferation. The viewer is drawn into bodily negotiation with modular tensions and spatial transformations (Foster 1996, 39).

Rauschenberg’s engineering of object relations opened the possibility of modular, unstable structures within a material field. Veech radicalizes this principle: engineering modular systems that are materially unified, relationally dynamic, and perceptually operative without recourse to symbolic narrative.

The radical destabilization of architectural structure finds one of its most powerful articulations in the work of Gordon Matta-Clark. His building cuts of the 1970s, including works such as Splitting (1974) and Conical Intersect (1975), violently reconfigured architectural space by removing sections of existing buildings. Matta-Clark’s interventions exposed the latent instabilities of structures presumed to be permanent, rendering visible the voids, ruptures, and asymmetries that underlie constructed environments (Lee 2000, 88–95).

Matta-Clark’s cuts did not destroy buildings as acts of negation; rather, they reconstituted the experience of space. By slicing through walls, floors, and ceilings, he produced disorienting spatial situations where gravity, horizon, and enclosure became uncertain. The viewer’s movement through these spaces was no longer stabilized by architectural continuity; it was a negotiation of spatial fragments, voids, and unexpected sightlines. Architecture ceased to be a container and became a medium of cognitive dislocation (Deamer 2005, 212).

Stuart Veech’s work engages this legacy at a structural, rather than literal, level. His reliefs and modular constructs perform acts of structural dislocation within the logic of the object itself. The modules of Silent Syntax introduce internal offsets, asymmetries, and rotations that destabilize the perceptual and spatial coherence of the form. As in Matta-Clark’s interventions, the viewer is confronted with a field in which expectations of stability, symmetry, and closure are systematically undermined (Colomina 1992, 134).

Yet Veech’s divergence from Matta-Clark is crucial. Where Matta-Clark’s cuts are acts of incision — violent interruptions into pre-existing structures — Veech’s modular syntax generates instability from within. His structures are conceived from the beginning as metastable fields. There is no original stability that is then violated: instability is the primary condition of form. The viewers encounter a dynamic syntax that unfolds relationally through movement and perception (Foster 1996, 45).

Matta-Clark’s works often emphasized the social and political dimensions of architectural destabilization, critiques of property, urban decay, and institutional authority. Veech’s destabilization operates at a more ontological level. His works interrogate the very conditions under which spatial coherence and perceptual anchoring are possible. The rupture is not social commentary; it is structural exploration (Wigley 1998, 92).

Matta-Clark revealed the fragility and ideological construction of architectural space through acts of literal cutting, while Veech extends this exploration into the silent, continuous operations of modular syntax: building spaces that are fields of structural and cognitive indeterminacy.

The activation of the viewer as a co-producer of spatial experience — a crucial shift in post-minimalist practices — finds a sophisticated articulation in the work of Dan Graham. Through his mirrored pavilions, video installations, and architectural models, Graham developed structures that fold viewers into feedback loops of perception. Works such as Public Space/Two Audiences (1976) and his later Pavilions turn transparency, reflection, and material partition into mechanisms of relational instability (Graham 1999, 43–50).

In Graham’s structures, the viewer perceives themselves perceiving; space is mediated through layers of reflection and refraction, producing delayed or fractured self-awareness. The work is a dynamic system in which viewing itself becomes the event and architecture dissolves into perceptual operations.

This principle of viewer activation is essential for understanding Veech’s syntax. Like Graham, Veech constructs works that do not complete themselves independently of the viewer’s movement. His reliefs and rotating modules require bodily negotiation: each shift of position recalibrates the relational field of surface, light, and form. Stability is deferred through the structuring of perceptual instability.

The differences are nevertheless decisive. While Graham’s pavilions rely heavily on optical devices (mirrors, glass, surveillance technology) to fracture space and perception, Veech’s works achieve destabilization structurally and materially. The rubberized surfaces, rotational mechanics, and modular asymmetries create perceptual shifts without mediation through technological apparatus. The viewer’s experience remains rooted in direct spatial and bodily encounter.

Furthermore, whereas Graham’s feedback loops often produce a heightened self-consciousness — the viewer is made acutely aware of their role within a mirrored, surveilled system — Veech’s structures diffuse subjectivity. The viewer is not placed at the center of attention; they are dispersed within a metastable field. Perception becomes less about recognizing oneself and more about negotiating shifting relational tensions.

In this sense, Graham redefined space as a relational and perceptual system, whereas Veech extendedthis redefinition materially and structurally, building silent architectures where perception is activated through structural indeterminacy itself.

Andrea Zittel’s work introduces another essential dimension to the architectural thinking underpinning Stuart Veech’s practice: the creation of modular structures that reorganize everyday spatial experience. In her Living Units (1993–ongoing) and A-Z Wagon Stations, Zittel designs minimal, self-contained habitats that challenge normative conceptions of dwelling, comfort, and autonomy (Zittel 2005, 17–21).

Each of Zittel’s structures operates within strict formal and functional parameters: modularity, compactness, and adaptability. Yet these are not utopian proposals. The smallness, the rigid structuring of bodily activities, and the insistence on modular repetition reveal the constraints as much as the freedoms of spatial design. Her works expose how architecture frames and disciplines life (Colomina 1992, 140).

This dual awareness — structure as enabling and limiting — resonates deeply with Veech’s syntax. Like Zittel, Veech constructs modular systems that define fields of possibility rather than fixed outcomes. His modules rotate, offset, and destabilize to produce relational environments where perception is structured and challenged (Meyer 2001, 63).

Yet Veech’s approach remains fundamentally non-functional. While Zittel’s units still fulfill the promise of habitation — however constrained — Veech’s structures refuse any functional framing. They are pure relational constructs, operating without program, narrative, and assigned use. Their modularity is a mechanism for activating cognitive and spatial indeterminacy (Wigley 1998, 98).

Moreover, Veech’s modular fields differ from Zittel’s living systems by embracing instability at a more radical level. Zittel’s environments, however experimental, maintain a functional coherence; Veech’s reliefs and rotating systems deliberately unmoor coherence itself; they destabilize perception as a way of rethinking structural relation (Foster 1996, 49).

Thus, while Zittel’s modular architectures illuminate how structures frame existence, Veech’s modular syntaxes propose an existence structured around relational, perceptual, and cognitive drift.

The modular operations within Stuart Veech’s practice establish a relational field in which structural instability, asymmetry, and spatial recalibration unfold through calibrated repetition and rotational dynamics. This logic of modularity finds a critical interlocutor in Dorothee Golz’s sculptural and conceptual investigations of modular objects and classificatory systems. While Golz’s practice remains distinct in materiality and referential scope, the operative parallels between her modular constructs and Veech’s metastable structures open a productive field of comparison, foregrounding modularity as a syntax of relational potentiality, a system in which classification and combination function as structural acts rather than taxonomic closures (Ermacora and Golz, 2014, 67).

Golz’s modular objects articulate a structural logic in which form is constituted as a systemically organized relational field. Across her sculptural and installation works, Golz constructs modular units whose capacity for recombination exceeds any singular configuration, generating an open taxonomy in which each element functions simultaneously as object, component, and relational node. The modularity at stake in Golz’s practice permits variation and establishes a principle of structural potentiality, where form emerges as a contingent articulation within an operative matrix of possible configurations (Ermacora and Golz, 52).

The Objektarchiv (Object Archive) exemplifies this structural operation: a corpus of modular objects arranged according to an internal classificatory logic that resists closure. The archive is a system of relational differentials in which objects, sculptural modules, constructed forms, and hybrid artifacts circulate between positions without final anchoring. Classification here generates structural tension between part and whole, module and system, and individual articulation and systemic field. The archive functions as a dynamic syntax in which each object maintains both autonomy and relational incompleteness, situating Golz’s modularity within a broader critical interrogation of taxonomic and epistemic structures (Wiener Secession 1996).

In Stuart Veech’s modular syntax, the operative affinities with Golz’s modular constructs become apparent through the shared structural condition of relational instability. Like Golz’s modular objects, Veech’s modules never stabilize into a totalizing composition: they remain situated within a metastable field in which each rotation, offset, and asymmetry recalibrates the structural relation without resolving it. Whereas Golz’s classification system constructs a field of shifting positionalities within an epistemic archive, Veech’s modular system constructs a field of shifting perceptual, spatial, and material relations within an architectural syntax. Both practices resist closure by structuring instability as an operative condition. Golz’s taxonomic openness and Veech’s spatial instability articulate two vectors of modular syntax: one toward classificatory potentiality, the other toward relational destabilization. Both unfold as silent structures in which modularity ceases to be a means of repetition and becomes a condition of structural becoming.

Lebbeus Woods advanced a conception of architecture no longer bound to stability, enclosure, or functional certainty. His speculative projects — such as Aerial Paris (1989) and War and Architecture (1993) — envisioned fragmented, unstable structures that embraced rupture, contingency, and the incomplete as fundamental conditions (Woods 1997, 11–16).

For Woods, architecture was not the construction of order against chaos but the dynamic negotiation of chaos. His drawings and models depict architectures fractured by forces internal and external (gravity, war, decay) generating spaces that are provisional, tense, and perpetually becoming. Spatial coherence is abandoned in favor of structural resilience within instability.

Veech’s modular syntax shares this refusal of stable completion. His reliefs and rotations generate forms that never settle into total coherence; their modular offsets, asymmetries, and shifting geometries stage a permanent tension within the very construction of form. Like Woods, Veech embraces instability as a structural principle and operative condition.

Veech’s divergence from Woods is equally sharp. While Woods’s architectures dramatize instability at the level of narrative imagery — buildings appearing as though wounded, fractured, or suspended — Veech internalizes instability within material and perceptual operations. His modules enact relational instability through precise, engineered dynamics. The experience of instability arises from bodily negotiation with metastable fields (Meyer 2001, 62).

Stuart Veech’s silent syntax avoids the theatricality sometimes latent in Woods’s speculative visions. There is no grand narrative of disaster or survival. Instead, Veech’s works generate quiet, continuous disruption: forms subtly resist perceptual closure, spaces shift without announcement, and relations remain unresolvable — as constitutive conditions of structural thought (Foster 1996, 44).

Mary Miss’s environmental works from the 1970s onward introduced a critical rethinking of spatial experience, placing the viewer’s movement and bodily negotiation at the center of structural meaning. Works such as Perimeters/Pavilions/Decoys (1978) constructed networks of poles, walkways, mirrors, and earthworks that fragmented and redirected perception, forcing participants to move, recalibrate, and rediscover their position within the field (Senie and Webster 1992, 102-108).

Miss’s practice rejected the notion of sculpture as an isolated object. Instead, she built relational environments: spaces where material structures and human perception continuously intersected. The work did not exist apart from the viewer; it only came through movement, through the piecemeal accumulation of spatial impressions.

This activation of spatial syntax through bodily engagement is fundamental to understanding Veech’s modular constructs. Like Miss, Veech designs relational fields where form is physically negotiated: the rotating modules, offset geometries, and fluctuating light effects demand movement and recalibration. The viewer’s path through space, the constant adjustment of body and eye, generates the work’s perceptual reality (Foster 1996, 42).

Where Miss’s environments often emphasize an expanded horizontal field — the ground plane as a site of dispersion and redirection — Veech’s works operate more intensively through volumetric articulation. His reliefs protrude into space, generating dynamic spatial compression and release through modular rotations. The instability is dimensional, folding the viewer into constantly shifting axes of relation (Colomina 1992, 138).

Miss often integrates natural materials (wood, earth, water) to anchor her structures in ecological rhythms. Veech’s material language is taut, industrial, and non-organic. His relational fields are constructions of cognitive and perceptual tension within a radically structured environment.

While Mary Miss redefined space as a material field shaped by bodily negotiation, Veech intensifies this relational architecture, producing spaces where material precision and structural disequilibrium compel a new mode of silent, active world-making.

-

The silent modular syntax that structures Stuart Veech’s work finds its most dynamic articulation through two interdependent operations: rotation and light modulation. Rotation, within Veech’s structures, is not a mechanical addition or decorative variation; it is a structural agent that destabilizes form, producing a continuous field of perceptual drift. Light, similarly, becomes an active force that alters the experience of space and objecthood over time (Foster 1996, 37).

Before addressing the singularity of Veech’s operations, it is essential to briefly situate his work within the broader history of art’s engagement with movement and rotation. In the mid-twentieth century, kinetic artists such as Yaacov Agam and Jesús Rafael Soto introduced movement primarily through optical interactions and viewer engagement. Jean Tinguely constructed mechanical sculptures animated by motors, emphasizing the spectacle of autonomous movement. Alexander Calder’s mobiles explored suspended motion in three-dimensional space, while Victor Vasarely’s paintings produced the illusion of rotational dynamism across static surfaces. Earlier avant-garde experiments, such as László Moholy-Nagy’s Light-Space Modulator and El Lissitzky’s Proun Room, speculated on dynamic spatial relations through rotating or spatially shifting elements. In the 1960s, Hans Haacke created environmental systems involving air currents and mechanical destabilizations, further expanding the field of kinetic and environmental art (Popper 1968, 123–130).

Despite these precedents, none of these practices engineered wall-mounted modular reliefs whose very structural logic was organized around controlled rotation and modular asymmetry. In Agam, Soto, and Vasarely, movement remains largely optical, relying on the viewer’s position to activate illusions of shifting form. In Tinguely and Calder, rotation becomes a mechanical spectacle, emphasizing motion for its own sake rather than as an integral structuring principle. In Moholy-Nagy, Lissitzky, and Haacke, movement is speculative or environmental, not embedded in the material articulation of relief-based form (Brougher 2005, 64–68).

In this context, Stuart Veech’s approach is radically singular. His rotation is neither optical illusion nor mechanical spectacle; it is a silent, materially disciplined operation that transforms structural relations directly. Rotation in Veech’s works destabilizes the viewer’s visual anchoring and the very conditions of modular coherence. As his reliefs rotate, their geometries shift, their symmetries fracture, and their relational fields reorganize, producing a continuous negotiation between material, space, and perception (Colomina 1992, 136).

Veech’s work acknowledges the historical engagement with movement and rotation, but it departs decisively from these traditions. In Silent Syntax, rotation becomes a fundamental syntax of relational instability, inextricably linked to the structural, material, and cognitive operations of the work itself (Meyer 2001, 59).

In Stuart Veech’s works, rotation functions not only as a kinetic action but as a structural reconfiguration of form. Each rotational movement subtly alters the relational geometry of the work: symmetries displace, alignments fracture, and surfaces reorient themselves relative to the viewer’s position and the surrounding spatial context. Rotation introduces a temporality into the perception of form, producing a continuous drift that resists stabilization. The modular elements, though materially stable in themselves, generate shifting fields of provisional order (Deleuze 1993, 14).

This structural use of rotation distinguishes Veech’s practice from earlier engagements with movement, where rotation often remained either a mechanical spectacle or an optical phenomenon. In Veech’s reliefs, rotation is integral to the production of meaning. It is through rotation that the viewer experiences the form as dynamic syntax rather than a static object. Each rotation constitutes a rearticulation of the work’s internal relations, compelling the viewer to renegotiate their spatial and perceptual anchoring (Foster 1996, 41).

Light is inseparable from this rotational dynamic. Veech’s surfaces, rubberized and semi-matte, interact with ambient light in ways that destabilize the perception of solidity. Depending on the angle of incidence and the viewer’s movement, surfaces may appear to absorb light completely or to reflect it with muted intensity, creating subtle variations in tone, texture, and spatial depth.

Aleksandr Rodchenko’s Black on Black (1918), often taken as a closure within painting’s trajectory, inaugurates a structural operation in which surface functions as an active relational field. The black monochrome is not reducible to optical flatness; it deploys material black as an operative condition, mobilizing absorption, reflectivity, and light modulation to construct a dynamic interaction between viewer and surface. This activation, grounded in faktura, inscribes material texture as syntax: a set of structural parameters through which perception and cognition are organized at the level of encounter (Lodder 1983, 89–92).

Rodchenko’s claim to have reduced painting to its “logical conclusion” has been read as negation, but the surface of Black on Black reveals a productive destabilization. The tonal shifts inscribed as crossing linear elements generate directional tensions, displacing any static reading of the monochrome. Lineism becomes the inscription of force, the construction of a relational field where form is constituted through the silent interplay of material, light, and vectorial displacement (Douglas 1990, 113). The surface ceases to be a site of compositional stability and emerges as an unstable matrix of structural relations.

This operative logic persists, reconfigured, in Stuart Veech’s modular syntax as transposed structural activation. Veech’s black rubberized surfaces, like Rodchenko’s black field, refuse pictorial depth; they construct a condition where surface materiality becomes a field of relational instability, absorbing and scattering light to unsettle perceptual anchoring. Where Rodchenko’s vectorial displacements remain within the pictorial plane, Veech extends these operations into three-dimensional, modular, and rotational structures. The silent operations of Rodchenko’s intersecting lines unfold in Veech as modular offsets, asymmetrical rotations, and surface articulations that activate perceptual drift across spatial axes. Rotation constitutes here a structural destabilization in which symmetry, alignment, and closure remain continuously deferred (Bois and Krauss 1997, 19).

The ideological alignment between material construction and collective production embedded in Rodchenko’s non-objective painting undergoes a fundamental displacement in Veech’s structures. While Rodchenko’s Black on Black sustains a utopian horizon, anchoring material syntax within a social imaginary of constructive production (Lodder 1983, 97), Veech’s modules retract from any projective function. His structures enact structural potentiality without prescriptive end. The modular rotations construct a metastable field, a syntax of relational instability that unfolds as perceptual negotiation without functional determination. The black surface is activated as a silent operational matrix where relational forces remain suspended in continuous recalibration.

Rodchenko’s non-objective syntax thus persists in Veech as an operative principle, transposed from planar faktura to architectural, modular, and rotational articulation. The black field becomes the generative condition through which structural relations unfold in silence, without finality.

Ad Reinhardt’s Black Paintings (1954–1967) constitute a structural operation in which surface enacts an interior destabilization that withdraws form from immediate legibility without relinquishing its presence. What appears as a flat black monochrome discloses, under extended viewing, a latent geometry: subtle cruciforms, tonal quadrants, and chromatic differentials emerging just within the limits of perceptual discernment. The black surface is concealment: form recessed into perceptual brink, demanding a durational, embodied encounter to render visible what remains structurally operative beneath optical opacity (Bois 1993, 131–135). The blackness of Reinhardt’s paintings functions as a material condition through which relational structures persist under erasure. Geometry here is withdrawn, folded into the silent operations of surface, waiting to be unfolded through the patient negotiation of light, time, and bodily proximity.

The claim toward a “last painting,” the painting beyond painting, installs Reinhardt’s black as a paradox: an object whose structural relations continue to operate while remaining partially concealed, an abstraction that refuses overt articulation yet cannot dispense with form. The black cross structures embedded within the surface act both as compositional scaffolding as well as residual syntax: minimal relational tensions that keep the field from collapsing into undifferentiated flatness. Reinhardt’s black is a field of suppressed relation, a zone where form resists disappearance without allowing its full emergence (Reinhardt 1966, 82).

In Stuart Veech’s modular structures, this latent structurality is transposed from the pictorial to the architectural, from the chromatic to the material, and from latent geometry to active modulation. The black surface in Veech’s reliefs externalizes structural instability through rotational dynamics, modular offsets, and material articulation. The perceptual threshold that Reinhardt’s black demands from a stationary viewer transforms in Veech into a spatial negotiation in which each bodily displacement, each shift in light, recalibrates the relational field. Where Reinhardt’s black requires stillness to activate perception, Veech’s black requires movement; where Reinhardt’s cross structures withdraw into a plane of delayed recognition, Veech’s modular rotations project asymmetry into volumetric space, displacing stability into metastable operations across depth and orientation (Colomina 1992, 136).

The relational difference is between structure concealed within a plane and structure enacted across modular, spatial, and perceptual axes. Reinhardt’s work sustains a logic of interiorization; Veech’s practice unfolds as a logic of exteriorization. The latency of geometry in Reinhardt becomes the operational openness of modular syntax in Veech, an abstraction that generates a dynamic topology of contingent relations. Reinhardt’s blackness demands the eye’s patient endurance; Veech’s blackness demands the body’s continuous negotiation. The surface in Reinhardt contracts relation into an intimate perceptual interior; the surface in Veech expands relation into an architectural field, activating light, material modulation, and spatial asymmetry as structural operators.

Veech’s silent syntax cannot be understood as an extension or negation of Reinhardt’s black. This syntax must be situated as a transposition of its latent operations into a structural field that refuses pictorial closure by dispersing relational stability into continuous recalibration. Black ceases to signify terminality; it becomes the operational matrix through which material, space, and perception co-construct an unstable, metastable field. Where Reinhardt’s black functions as an endgame, a distillation of painting into its non-objective limit, Veech’s black reactivates abstraction as a silent structuring of relational potential: a syntax of material, spatial, and perceptual relations unfolding without finality.

Here, the proximity to Pierre Soulages’s investigations of black surfaces becomes evident. In his Outrenoir paintings, Soulages revealed that black is not a negation of light but a field of active modulation, where the smallest shift in light or movement produces profound transformations in the surface’s appearance (Soulages 2007, 14–17). Similarly, Veech’s surfaces are not inert; they are active agents in the structural and perceptual field. Light, in this context, is not external to form; it is folded into its operational syntax.

In Veech’s practice, rotation and light function together as structural mechanisms that dissolve the objecthood of form. The artwork exists as a dynamic field of relations continuously generated and regenerated through material operations, spatial movement, and perceptual drift.

The structural destabilization achieved through rotation and light modulation in Stuart Veech’s work also finds critical historical resonances with the earlier experiments of Frank Stella and Robert Mangold, though Veech’s operations ultimately diverge and deepen these inquiries into new territories.

In Frank Stella’s early shaped canvases, particularly those of the Protractor Series, internal compositional logic generates forms that resist the traditional frontal stasis of painting. Stella’s works suggest centrifugal movement through the repetition of arcs, radii, and interlaced patterns, pushing the viewer’s perception toward a sense of outward, rotational dynamism. Yet despite these internal movements, Stella’s canvases remain fundamentally planar and materially static. The optical destabilization occurs across a fixed surface, relying on the viewer’s eye to activate rhythmic motion within a bounded pictorial field (Stella 1986, 114).

Veech extends and transforms this principle. Rotation in Veech’s works is a structural operation that reconfigures the real spatial and material relations of form. Unlike Stella, where movement is visually induced but structurally absent, Veech embeds movement as a material condition, producing forms that drift, offset, and recalibrate as a direct consequence of their rotational logic (Meyer 2001, 62).

Robert Mangold’s segmented circles, partial frames, and broken geometries introduce a different kind of destabilization. In works such as the Attic Series, Mangold fractures the viewer’s expectation of closure and stability, introducing gaps, asymmetries, and interrupted continuities into the formal language of minimalist geometry. However, as with Stella, Mangold’s destabilizations remain graphic and frontal. They unfold within the two-dimensional plane, relying on the interpretative activity of the eye rather than on the structural reconfiguration of material space (Mangold 2000, 12–15).

Veech moves this destabilization from the graphic to the architectural. His rotations and modular articulations physically fragment and rearticulate space itself. The viewer’s experience is a bodily negotiation of shifting material relations: as the viewer moves and as the object rotates, the relational field continuously evolves, rendering any fixed reading provisional (Colomina 1992, 136).

An earlier conceptual precedent for this materialization of spatial instability can be found in El Lissitzky’s Proun works and his theorization of dynamic space. Lissitzky imagined a dissolution of traditional pictorial stability through spatial constructions that rotated and reoriented the axes of perception. His Proun Room (1923) extended these investigations into an immersive environment where the viewer’s bodily movement would engage the tension of spatial coordinates (Perloff, 1985, 11-12). However, Lissitzky’s proposals remained largely conceptual and speculative, realized primarily through painting, relief, and limited three-dimensional constructions.

Veech carries the implications of these early modernist experiments into fully realized operative logic. His modular works perform rotational instability. Rotation and light are material engines of perceptual drift. In this way, Veech’s practice does not simply follow from the experiments of Stella, Mangold, or Lissitzky; it transfigures their latent ambitions into an operative and continuous dynamic field.

Stuart Veech’s practice cannot be adequately captured by either post-minimalist or post-post-minimalist frameworks. It emerges instead as a distinct structural field in which modularity, rotation, and light are operationalized. His works propose an abstraction as an active world-making: a syntax of relations unfolding silently, materially, and structurally through perceptual drift (Bois and Krauss 1997, 36).

-

The materiality of Stuart Veech’s practice is neither neutral nor decorative; it is central to the operational field of Silent Syntax. Every surface, every joint, and every rotational mechanism participates in the construction of a relational structure that refuses overt symbolism or expressive excess. In Veech’s work, material itself becomes syntax: a silent agent through which perceptual, spatial, and cognitive relations are enacted (Bois and Krauss 1997, 39).

The disciplined use of rubberized surfaces exemplifies this principle. Veech’s surfaces, often matte or semi-reflective, modulate light in ways that destabilize the viewer’s perception of form. Depending on the incidence of light and the angle of approach, these surfaces absorb, diffuse, or reflect light differentially, producing subtle but continuous shifts in visual reading. The surface quietly recalibrates the relation between object, space, and viewer (Soulages 2007, 14–17).

This active modulation of surface echoes Pierre Soulages’s investigations into the dynamic interaction of black and light, but in Veech’s practice, the material is even more tightly integrated into structural function. Light participates in the production of relational fields. The boundary between surface and space becomes permeable, and form is experienced as a dynamic interplay of material, light, and movement (Foster 1996, 42).

The modular construction of Veech’s works further reinforces this material structuring. Each module is precisely engineered, its joints and rotations calculated to maintain a structural coherence that nonetheless produces relational instability. Unlike post-minimalist works that emphasize process, material pliancy, or improvisational assembly, Veech’s modules assert a deliberate, rigorous logic: they are precise mechanisms for generating perceptual drift (Meyer 2001, 62).

This structural exactitude produces an intense intimacy of experience. The viewer’s movement, attention, and cognitive engagement are drawn into the silent operations of the work. Perception becomes an active, world-constituting act, unfolding through relational negotiation (Colomina 1992, 137).

Thus, material silence in Veech’s practice is the condition for a different kind of world-making. It is through the disciplined material articulation of modularity, rotation, and light that Silent Syntax enacts its field: a world constructed through structural relation and perceptual reorientation.

The world that Stuart Veech’s Silent Syntax constructs is a world generated through the continuous unfolding of structural relations. In this sense, world-making is a material and perceptual operation. The viewers co-construct it through their engagement with modular drift, rotational instability, and light modulation (Noë 2004, 1–3).

Central to this operation is the displacement of stability as a foundational category. In traditional sculptural and architectural thought, form is anchored through mass, gravity, and orthogonal relations. Stability becomes the silent guarantor of space’s intelligibility. Veech inverts this logic: his modular fields are materially stable in the sense of engineering precision but perceptually and spatially unstable. Rotation shifts symmetries, light fractures surface coherence, and movement reconfigures relational fields. The viewer cannot settle into a singular, totalizing grasp of form. Instead, perception itself must remain mobile, flexible, and open to continuous recalibration (Foster 1996, 38).

This demand for perceptual mobility shifts the role of the viewer fundamentally. In minimalist practice, the viewer’s bodily movement already played a role in activating the object’s spatial presence, as in the works of Donald Judd or Carl Andre. Yet there, the object maintained its internal stability; movement was revealedbut did not alter the object’s structural logic. In Veech’s practice, movement is not a passive act of revelation but an active constitutive force. The work exists as a relational field that only comes fully into being through bodily negotiation (Meyer 2001, 57).

Importantly, this world-making does not rely on subjective projection or interpretative freedom in the postmodern sense. Veech’s modules are not open-ended invitations to narrative play. These works are precise structures that constrain and channel perception through their silent operations. The world they produce is one of disciplined instability: a field where structure, material, light, and movement form a contingent but rigorously articulated space (Colomina 1992, 139).

Consequently, in Silent Syntax, material silence is a reconfiguration of meaning’s conditions. World-making occurs through the dynamic activation of structural relations in space and time (Grosz 2001, 126). Meaning in Veech’s work emerges through the active negotiation of tensions, rotational shifts, and light-mediated perceptual drift (Bois and Krauss 1997, 36).

This mode of abstraction differs sharply from earlier modernist strategies. In the traditions of geometric abstraction, from Kazimir Malevich to Piet Mondrian, abstraction often sought to purify form, to strip away the contingencies of representation, searching for a universal visual language. In Veech’s structures, by contrast, there is no aspiration toward universality. The modular systems are not purified; they are activated, and their meaning unfolds through contingent material, spatial, and perceptual interactions (Chave 1990, 56–58).

Similarly, Veech’s practice diverges from the post-minimalist turn toward material entropy and subjective embodiment. His modular articulations are disciplined fields in which relational instability is structurally embedded, not left to material improvisation. The experience of drift and dislocation is produced through precise, engineered operations rather than through the inherent behavior of unstable materials (Meyer 2004, 27).

In this sense, Veech’s abstraction can best be understood as an operative abstraction. Each module, surface, and rotational mechanism contributes to the construction of a rigorously articulated world.

Material silence in Veech’s practice is thus the silence of structural generation, abstraction becoming the very condition of world-making itself (Bois and Krauss 1997, 36).

-

Stuart Veech’s Silent Syntax establishes a paradigm in which abstraction is no longer a matter of reduction, resistance, or symbolic displacement. It is redefined as the operative construction of relational fields: modular, dynamic, materially silent, and perceptually generative. His work does not extend historical abstraction by reinterpretation; it reconstructs its conditions of possibility at the level of structural action (Bois and Krauss 1997, 36).

In Veech’s practice, form is placed into a state of metastability: a condition in which structural precision generates continuous perceptual reorientation without abandoning material rigor. Rotation is not movement for its own sake; it is an operation that fractures and recalibrates the syntax of modularity, while light is a structural agent that transforms surface and space into dynamic perceptual fields (Deleuze 1993, 14).

This mode of abstraction disengages from the dialectics of minimalist objecthood and post-minimalist material contingency alike. Veech’s structures anchor instability within material articulation itself, producing a field that demands movement and negotiation (Meyer 2001, 57).

Silent Syntax thus proposes a new operative logic: a syntax of material relations that constructs a world without representing it, a space where abstraction is realized as structural, cognitive, and bodily activation.

Silent Syntax establishes a contemporary paradigm in which abstraction is no longer a visual style or historical gesture but becomes a structural operation. In Veech’s practice, form is constructed through modular articulation, relational destabilization, and the activation of perceptual drift. The artwork it is a dynamic syntax that materializes structure as cognitive and spatial negotiation (Colomina 1992, 135).

In this framework, abstraction is a mode of constructing real, operative fields — fields in which material, movement, and perception are inseparably bound. Veech’s Silent Syntax thus marks a decisive shift: from the static autonomy of form to the active production of structural relations as the primary condition of abstraction itself.